Opening up the conversation: when external experts share practice and research

Published on 28.04.17

Thanks to Neil Hadfield, the leader of our BA (Hons) Illustration course, who invited Dr. Peter Wakelin and Clive Hicks-Jenkins to HCA last week. This was one of the most interesting events I’ve participated in this year. Peter’s talk took us on a fast-paced journey through Welsh landscape painting, with a focus on the romantic

Categories

Thanks to Neil Hadfield, the leader of our BA (Hons) Illustration course, who invited Dr. Peter Wakelin and Clive Hicks-Jenkins to HCA last week. This was one of the most interesting events I’ve participated in this year.

Peter’s talk took us on a fast-paced journey through Welsh landscape painting, with a focus on the romantic and neo-romantic movements and how these interpreted and re-interpreted the particular resonances of the Welsh landscape. Threaded through his talk were the stories of the painters and their rich legacy; continued today with the work of contemporary artists such as Bert Isacc and David Tress.

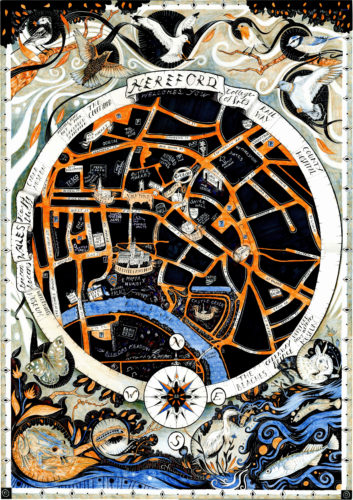

Clive’s presentation showed the stories behind his work, but he also shared his process – his research-as-practice and the concept behind a range of paintings and prints. He discussed the links between illustration and narrative painting and stressed the importance of collaborations with people from different disciplines- from poets to publishers.

He talked of the stories, characters and dilemmas that inspire him, sharing with us his pictures of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, his love of the Simon Armitage translation of this ancient poem and his personal perspective and characterisation of the stories, expressed in a particular and personal visual language.

Both presentations were entertaining, scholarly and insightful. Clive’s sharing of his process in developing narrative art reminded me of Healey, Jenkin’s and Lea’s 2014 research around developing research-based curricula in college-based Higher Education. Their work mentioned the importance of lecturers sharing their personal research processes with students as a useful learning conversation. It made me think how lucky we are to be part of this wider learning ecosystem where highly successful visual artists are so willing to share their practice-as-research and academic research with students.

From a teaching and learning perspective, it would be easy to see Thursday’s work as a ‘lecture’; the audience ‘consuming’ knowledge from expert professionals. But although the physical trappings of the room ‘looked’ like the lecture – the seats in rows, a large projector, a podium, this was not knowledge consumption. Knowledge was shared and shown, not taught and told. Our students, coming from a relatively small HE community, had different perspectives and ideas brought to them and, as you can see from the instagram photos below – were able to look at examples of work-in-progress. I was reminded of our student governor’s comments during the writing of the TEF contextual statement that we ‘mustn’t forget the value of our big lectures.’

The idea of the ‘big lecture is perhaps representative of antiquated pedagogies. However, although an education formed entirely of lectures is certainly not desirable, perhaps as one aspect of our teaching it maintains a relevance, particularly if presenters ‘show’ rather than ‘tell’ – as was the case on Thursday.

There may also be the argument that more ostensibly ‘formal’ settings, as an occasional feature of the learning environment, support the acquisition of social capital in a way that only providing workshop-based or small group learning does not. After all, how many conferences are still built mainly on a traditional presentation model, particularly in the keynotes? If students from non-traditional backgrounds have never experienced a traditional ‘presentation’ how will they develop strategies (such as good note-taking skills) that make them feel comfortable in such learning environments? What, then, if they enroll in an M.A programme that is heavily reliant on the lecture model?

Perhaps one of the key benefits of an arts education is that scholarship takes place in a range of learning environments, from the lecture through to the studio, the exhibition to the workshop. The fluidity that can occur as students move between these environments, engaging in multiple conversations in different contexts supports all four of Boyer’s dimensions of scholarship.

We are also, of course, very lucky to have professionals working in college who know such interesting people and particularly for the generosity of external professionals like Clive and Peter who freely shared their fascinating ideas, research and practice with all of us on Thursday.